Likable Leads: How To Write Movie Protagonists That Connect (With Examples)

The note on your screenplay comes in many forms:

“I’m just not with the main character.”

“The protagonist is not very likable.”

“I’m not connected to their journey.”

“I don’t care enough about them.”

All of these comments boil down to this: your lead character just isn’t jumping off the page and connecting with your reader.

Tara and I have gotten ALL of these notes over the course of our writing career. And if you’re courageous enough to write a script (go you!) you’re going to get them too.

So what do you do? How do you create a likable protagonist in the first few pages that jumps off the page and into the heart of your reader? Here are some ideas to help you write a main character that connects.

Make Your Lead Character The Victim Of Misfortune.

Conflict is the engine that makes a screenplay work. And conflict needs to start on page one, scene one. When there’s no conflict (either internal or external), there is only boredom.

One way to create conflict for your main character is to make them the victim of misfortune right off the bat.

They could miss the bus because the bus driver doesn’t like them and closes the door in their face. They could be late for work because their car wouldn’t start and no one would give them a boost. They could be forced to change their clothes because they spilled yogurt on themselves moments before a huge meeting.

All of these misfortunes work to build sympathy for your lead. Michael Hauge writes in his book, Writing Screenplays That Sell:

“If you can get the reader to feel sorry for your hero by making her the victim of some undeserved misfortune, you will immediately establish a high degree of identification with that character.”

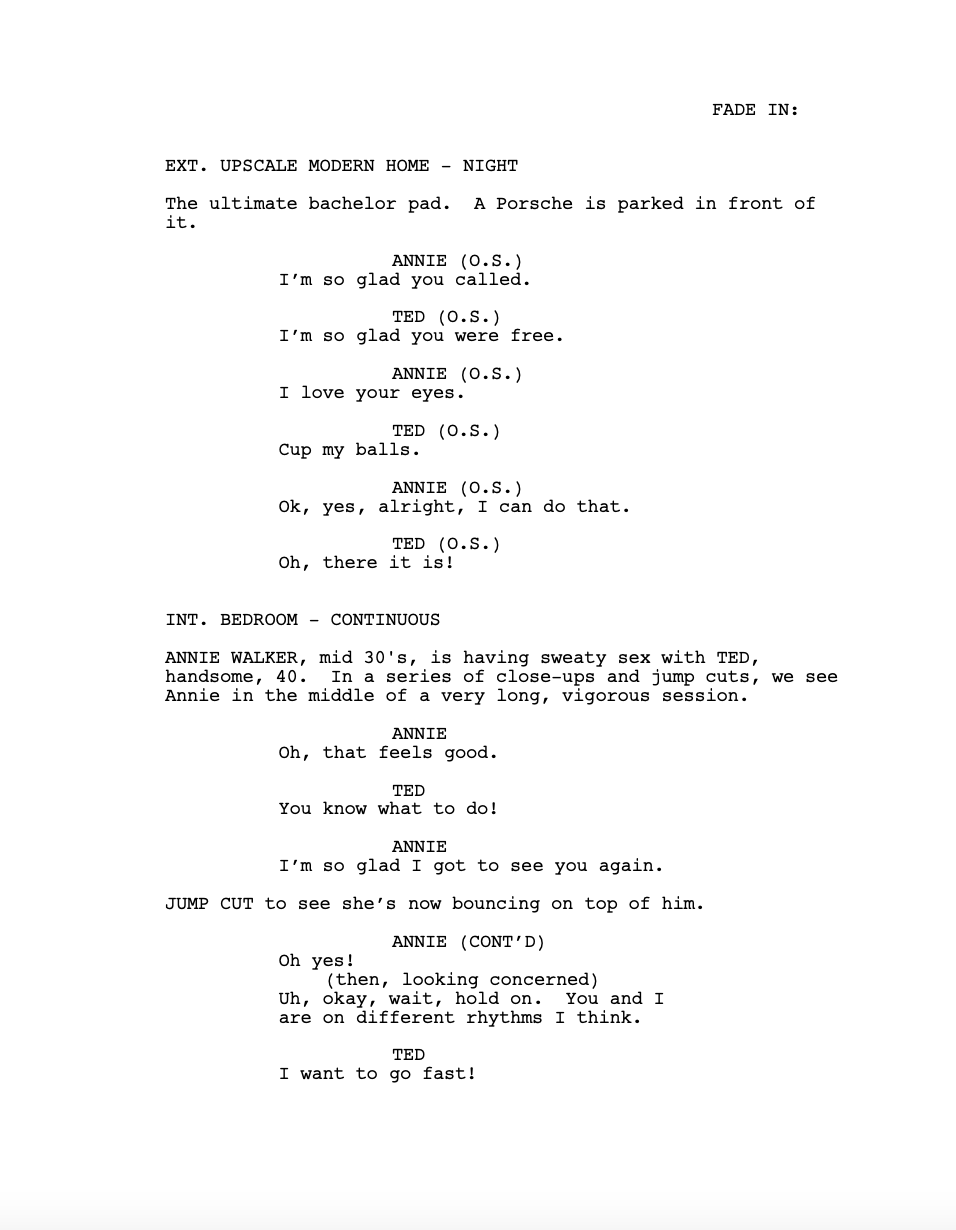

Here’s an example of creating sympathy for a lead character in the opening scene of the screenplay, Bridesmaids, by Annie Mumolo & Kristen Wiig:

Here, we identify with Annie (and feel sorry for her) because Ted treats her like shit. It’s clear Annie really likes Ted and is trying to win him over, but he’s an asshole and is just using her for sex. That makes us hate Ted and like Annie, all in the opening three pages.

Put Your Protagonist In Physical Danger.

While comedies and dramas tend to use sympathy to get us in sync with the lead, action and adventure movies often use physical danger. You’ll see this in the opening sequences of the James Bond films, Indiana Jones movies, and countless other adventure flicks. Here’s Hauge again:

“Closely aligned to creating sympathy for the character is getting the reader to worry about your character by putting her in a threatening situation.”

Here’s an excerpt from the classic opening to Raiders Of The Lost Arc (Screenplay by Lawrence Kasdan, Story By George Lucas) that shows how effective this technique is.

By page three, Indy’s “partners” are already plotting to kill him. This creates suspense and empathy in the reader because we know their plan, while Indy doesn’t. On page 4, Barranca tries to murder our lead (of course, Indy has the faster hand).

Putting Indy in this much danger so early in the script helps us identify with him. While we know intellectually he’s not going to be killed in the first few moments of the movie, we still worry for him. It also reinforces how skilled Indy must be if everyone is trying to kill him - he must have something other men don’t have that threatens them.

Make Your Lead Funny.

This is the one Tara and I use the most (along with misfortune) because we write comedies. If you can make your character funny on page one, that will go a long way in getting the reader engaged with your lead, even if they’re not a “good” person.

George Constanza is a great example of this. He’s one of the most despicable characters ever written… and also one of the funniest. Here’s Adam McKay talking about this in Poking A Dead Frog:

“There’s no greater comedy killer than receiving a note that says a character’s not likable enough. The second you see someone write that, you know they don’t know a thing about comedy. The entire game is to make your character as awful and irresponsible as possible, while still keeping a toe in the pool of his still being a human being… The more despicable your guy can get away with behaving while still remaining on the side of the audience, the funnier it’ll be. Seinfeld is the greatest example of that ever.”

Notice how it works in the Bridesmaids scene above. How can you not love a character who puts on a full face of make-up just to pretend she woke up like that?! Sure, it’s a little vain, but it’s FUNNY. And that goes a long way.

Make Your Protagonist A Good Person.

It’s much easier for us to connect with a lead character if we see them trying to be a good person. And as a writer, you can do this by showing how your character treats other people. Erik Bork talks about how important this is in his book, The Idea:

“How do you make the main character likable? There’s one clear-cut area where a character’s behavior will make the audience either like or dislike them: how they treat others. If they are really good to others, even to the point of forgoing their own interests at times, we will tend to instantly like them. If they are selfish and don’t go out of their way for others, we will tend to not like them.”

The pilot episode of Ted Lasso (Teleplay by Jason Sudeikis & Bill Lawrence) uses this technique masterfully. The first time we see Ted, he’s dancing in the dressing room with his players all around him. The teleplay reads: “We see Ted in a PHONE VIDEO, DANCING with his players. The connection between Coach Lasso and his team is palpable.” If Ted can win over these players as he has, he must be something special.

In the next scene, Ted is on an airplane and is just sitting down to read his book when a teenager shoves a phone in his face and asks for an “us-ie.” Here’s the excerpt:

Notice how Ted takes both the “us-ie” and subsequent trolling in stride. He’s not rude or combative, and treats the kid with far more respect than he deserves. How can you not like this guy? He knows exactly who he is and isn’t bothered by anyone else’s opinions.

Another way to approach this kind of opening is via Blake Snyder’s “Save The Cat” technique. Snyder claims that if you have your lead do something nice in the opening pages - if you show them being a good person - then we’ll like them. Here’s Snyder explaining it:

“Liking the person we go on a journey with is the single most important element in drawing us into the story. I call it the ‘Save the Cat’ scene. They don't put it into movies anymore. And it's basic. It's the scene where we meet the hero and the hero does something - like saving a cat - that defines who he is and makes us, the audience, like him.”

Give Your Lead A Best Friend Who Likes Them.

This is used often in comedies and romantic comedies. Giving your main character a best friend and confidant who always has their back and will do anything for them immediately establishes that your hero is worth caring about.

Ted Lasso does this with Coach Beard. We immediately get a sense of how close these two are, not just as coaches but as friends. Here’s the scene:

Not only is that last line about seeing each other in their dreams one of the best lines I’ve ever read, but Coach Beard literally says to Ted: “I owe you a lot and you know I’d follow you anywhere.” If Beard cares this much about Ted, the audience will too.

Make Your Lead Character Great At Something.

We love watching people who are at the top of their professions. James Bond is James Bond because he’s the best secret agent in the world. All of the Oceans movies are fun to watch because you see a collection of characters who all have a “special ability” - something that sets them apart and makes them perfect for the heist.

Here’s Hauge again from his book:

“We are naturally drawn to people who are talented, who are masters at what they do. Show the character in touch with his own power. Power over other people. Power to do what needs to be done, without hesitation. Power to express one’s feelings regardless of others’ opinions.”

This is especially useful if your character is a “bad guy.” You can still create empathy for your villains and antagonists by showing us how incredibly good they are at what they do.

Give Your Protagonist A Major Flaw.

Every human is flawed, and when we see our flaws in a fictional character, we connect with them. “Perfect” characters are boring, and worse, they don’t represent the truth.

So give your character lots of flaws. Make them too obsessed or too optimistic (Ted Lasso). Let them be ignorant or naive about how the world really works (Rachel in Friends). Make them control freaks who suffer each day to bend the world to their will (Melvin in As Good As It Gets). Or make them the opposite: too passive. They’re waiting for their life to start instead of jump-starting it themselves (almost every lead in Judd Apatow movies).

Flaws are what make us human. Use them in your lead character to capture your reader.

Let Us Experience The World Through The Eyes Of Your Lead.

This is one of the big mistakes Tara and I made while writing our first feature. We had a lot of scenes AWAY from our lead character. We weren’t learning information as she was, and thus we weren’t experiencing the impact of what was happening from her point of view.

If you stick close to your lead character and let us experience the story through them, you go a long way in building empathy with your reader. Here’s Hauge once more:

“Make your hero the eyes of the audience. Identification is sometimes strengthened when the audience only learns information as the hero learns it.”

This is easier to do if you only have one main character. Ensemble pieces are tough because each time you switch to a new character’s perspective, we have to identify immediately with their struggle or we’ll lose interest.

So stick to your lead like glue and let us experience the world through their eyes.

Make Your Protagonist’s Motivations Clear.

This one is useful if your character is a “bad guy” or isn’t necessarily “likable.” If you give us the “why” behind your character’s actions - even if we don’t like those actions - you can build empathy for your character.

Here’s John Truby writing about this in his book, The Anatomy Of Story:

“What’s really important is that audiences understand the character but not necessarily like everything he does. To empathize with someone means to care about and understand him. That’s why the trick to keeping the audience’s interest in a character, even when the character is not likable or is taking immoral actions, is to show the audience the hero’s motive.”

For example, James Bond villains often have a distorted “why” to their actions that are revealed over the course of the movie. This “why” is often based around some traumatic experience in their past aimed at building empathy for the antagonist.

So give us your character’s motivation for wanting what they want, and we’ll often go along for the ride.

—

ARTICLE SOURCES

Poking a Dead Frog: Conversations with Today’s Top Comedy Writers, By Mike Sacks

Save The Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You'll Ever Need, By Blake Snyder

The Anatomy Of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Storyteller, By John Truby

The Idea: The Seven Elements of a Viable Story for Screen, Stage or Fiction, By Erik Bork

Writing Screenplays That Sell: The Complete Guide to Turning Story Concepts into Movie and Television Deals, By Michael Hauge